This past September, I drove out with Pat Hanson, director of the firm Gh3*, to see her most recent Toronto build, a sculptural folly in the city’s Port Lands district. A 13.5-metre-tall cylindrical concrete column with four arched openings, it affords sweeping views of Leslie Lookout Park, a new public space by the late, great landscape architect Claude Cormier. The park is paved with asphalt, the permeable kind that absorbs rainwater, and it features a sandy expanse on a shipping channel. On one side is a suite of silos belonging to a concrete manufacturer; on the other are mountains of dusty aggregate. “It’s a great place to have a beach,” Hanson said, without a hint of irony.

It’s also a great place to view one of her designs, which look especially good in scrappy industrial contexts. Pat Hanson and Gh3* specialize in dusky, monolithic buildings, as clean as still water, as seemingly permanent as bedrock. Her simple forms connote rigour and honesty; her materials possess elemental beauty. Hanson’s folly in the Port Lands, with its thick concrete walls and simple apertures, harks back to a pre-Renaissance era before design got fussy and ornamental. On the day we visited the park, it was the main attraction, generating more intrigue even than the nearby Akira Miyawaki–inspired forest. Visitors were drawn to it, as if compelled by some primitive instinct to seek shelter behind fortified walls.

Hanson is getting used to success. She founded her now-26-member firm in 2006. This year, she was awarded the King Charles III Coronation Medal from the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada. When asked how many Governor General’s Awards her firm has won, she first has to pause to do some mental arithmetic (the number is five). The best thing about Gh3* is that it brings a boutique sensibility to large public works. While the firm does its share of private homes and businesses, its portfolio includes parks, garages and water treatment plants, many of which push the boundaries of sustainable design.

To get into the infrastructure game, Hanson has learned to win over bureaucrats — to be aesthetically resolute yet skilled in the art of the compromise. “She bears the cultural influence of Manitoba, where she studied, and Saskatchewan, where she grew up,” says John van Nostrand, founding principal of the Toronto firm SvN and a mentor to Hanson. People on the Prairies, he explains, have a kind of pragmatism that’s reflected in their no-nonsense work ethic, and also in their built forms, which are tough and durable and made for civic purposes. “In every village, there’s a grain elevator,” a tower constructed of hardy timber against a flat landscape, van Nostrand says.

Hanson never intended to start her own shop. In the ’80s, she worked for van Nostrand, who focused almost exclusively on affordable housing, then went back to her former employer, the Toronto stalwart Diamond Schmitt. She was eventually hired as a partner at architects–Alliance, a firm specializing in condos and hotels. Business was lucrative, but relationships at the top became tense, and Hanson felt pressure to resign. To finish off projects and ensure a good settlement, she continued coming in to work for eight months after giving notice. The experience, she says, was humiliating: “I was nearing 50, and I had no idea what I was going to do with my time.”

She knew this much, though: She would never work for anybody else again. Instead, she founded Gh3* with a landscape architect colleague. (The “G” was for her co-founder, the “h” was for Hanson, and the “3” represented the firm’s intended practice areas: landscape, architecture and urban design.) The goal was to carve out a niche as an integrated practice able to take on projects of any type and scale.

But the procurement process in Canada heavily favours incumbency. To be commissioned for, say, a fire hall, it helps to have designed two or three fire halls already. But you can’t build up that track record if nobody will hire you in the first place. That’s why most public buildings today are done by big institutional shops known more for dependability than excellence. In 2009, to stimulate the flagging economy, the federal government put out a slew of RFPs for university buildings. Gh3* submitted 20 applications. Each took two weeks of labour. None panned out.

Hanson hunted instead for under-the-radar opportunities, including an RFP from the municipal agency Waterfront Toronto to design — with the help of an engineering firm — a stormwater treatment plant near the lakeshore. The facility would gather rainwater from the surrounding catchment area through a system of pipes and ducts. It would then purify the water with filters and ultraviolet light before releasing it back into Lake Ontario. This process was a marked improvement on the common practice of simply allowing stormwater to mix with sewage, which risked overwhelming the plant that then flowed the polluted water back into the lake.

The project was so small and cheap that basically no one wanted it. But Hanson offered to do the architecture for a miniscule fee because she saw a chance to build something special. “I’ve done a lot of residential work in my lifetime,” she says. “But there’s only so much you can do with a home. You’re constrained. There are rules around bedroom sizes and windows.” A stormwater facility, though, is a mere container, a hard shell protecting mechanical systems from the outside world. She envisioned a simple rectangle with a prismatic roof, like a cistern turned inside out.

A second big opportunity came from Edmonton, perhaps the only municipality in Canada to put design excellence at the centre of its commissioning strategy. It helps that Edmonton has a city architect, a post held since 2009 by Carol Bélanger. “My mandate from then-mayor Stephen Mandel was simple: No more crap buildings,” he says. Applications in Edmonton are open to all firms, big and small, local and international. The price for each project is set by the city based on established guidelines, which means a firm can’t win a competition by lowballing its fees. Experience counts, of course, but so does talent. A young firm with a slim portfolio can compensate by putting in the best proposal possible.

That was Hanson’s strategy. When, in 2011, Edmonton announced competitions for five park pavilions across the city, she shut down her office for three weeks and told her staff, then nine, to focus exclusively on the proposals. They applied to all five competitions and won two, beating over a hundred submissions. Bélanger was bowled over by the tasteful simplicity of Hanson’s park buildings, both of which were completed in 2014. The circular pavilion at Borden Park, in the city’s northeast, resembles a mirrored drum or a carrousel.

The pavilion at Castle Downs Park, in the northwest, is a sprawling, low-lying structure clad in crinkly reflective glass, like a prairie mirage. The works, Bélanger says, were as fully realized in life as they were on paper. Deep into the construction of the Borden pavilion, he recalls, Hanson decided that the caulking between the mirrored panels was just a shade too dark. It would stand out, she reasoned, creating a visual distraction on an otherwise clean surface. “I told her, ‘We’re on a tight budget,’ ” Bélanger says. There wasn’t much he could do. So Hanson cut a cheque to the city, paying out of pocket for a new shipment of caulking.

Pretty much everyone who works with Hanson has an anecdote like this one about the lengths she will take to safeguard the integrity of her work. Brenda Webster, an urban strategist with the engineering firm Stantec and a former planner at Waterfront Toronto, had the unenviable job of steering the stormwater facility through completion, a process that took over a decade. At times, Webster doubted that the project would ever get built, because the city kept reducing the budget. One day, in desperation, she asked the engineers how much they would spend just to build a corrugated metal shack to house the core equipment.

They quoted her a figure for a prefab steel structure. She took it to Hanson, reasoning that it was at least a stable minimum. Improbably, Hanson made her original design work. Instead of putting a skin atop a structural wall, Hanson opted to use cast-in-place concrete on the outside of the building, where it would do double duty as both wall and wall cladding. “She did everything she could to keep that project alive,” Webster says.

The Storm Water Quality Facility (SWQF) finally opened in 2020 and went on to win the Governor General’s Award and the Civic Trust Award from the U.K., which has honoured international heavyweights like Enric Miralles, Benedetta Tagliabue and Daniel Libeskind. The building is simple, yet it possesses a quiet kind of dignity, with its monumental form and its clean surface shorn of visual blemishes. It also made a statement: Anything can be beautiful. No building, regardless of price or purpose, is so humble that it merit thoughtless design.

The SWQF was Hanson’s first public commission, but in the 12 long years between procurement and completion, her firm had evolved considerably. By 2017, the partnership between the two co-founders had broken down over an interpersonal dispute and Hanson terminated the relationship. (“It was tragic,” she says. “Depressing.”) She then added an asterisk to the firm’s name, enabling her to reincorporate it without losing the brand identity. By this time, she’d taken on several key principals: Raymond Chow, an image-maker of the highest order; Joel Di Giacomo, a wizard at 3D modelling software; and John

McKenna, a writer whose rhetorical skills give the firm’s proposals a competitive edge. She also has a director of landscape, Elise Shelley, who ensures that all of the landscape work is integrated seamlessly with the architecture. The brand had amassed some serious clout, too, thanks to a growing portfolio of even bigger Edmonton projects, each built around a succinct visual motif and featuring a single exterior material chosen for its evocative potential.

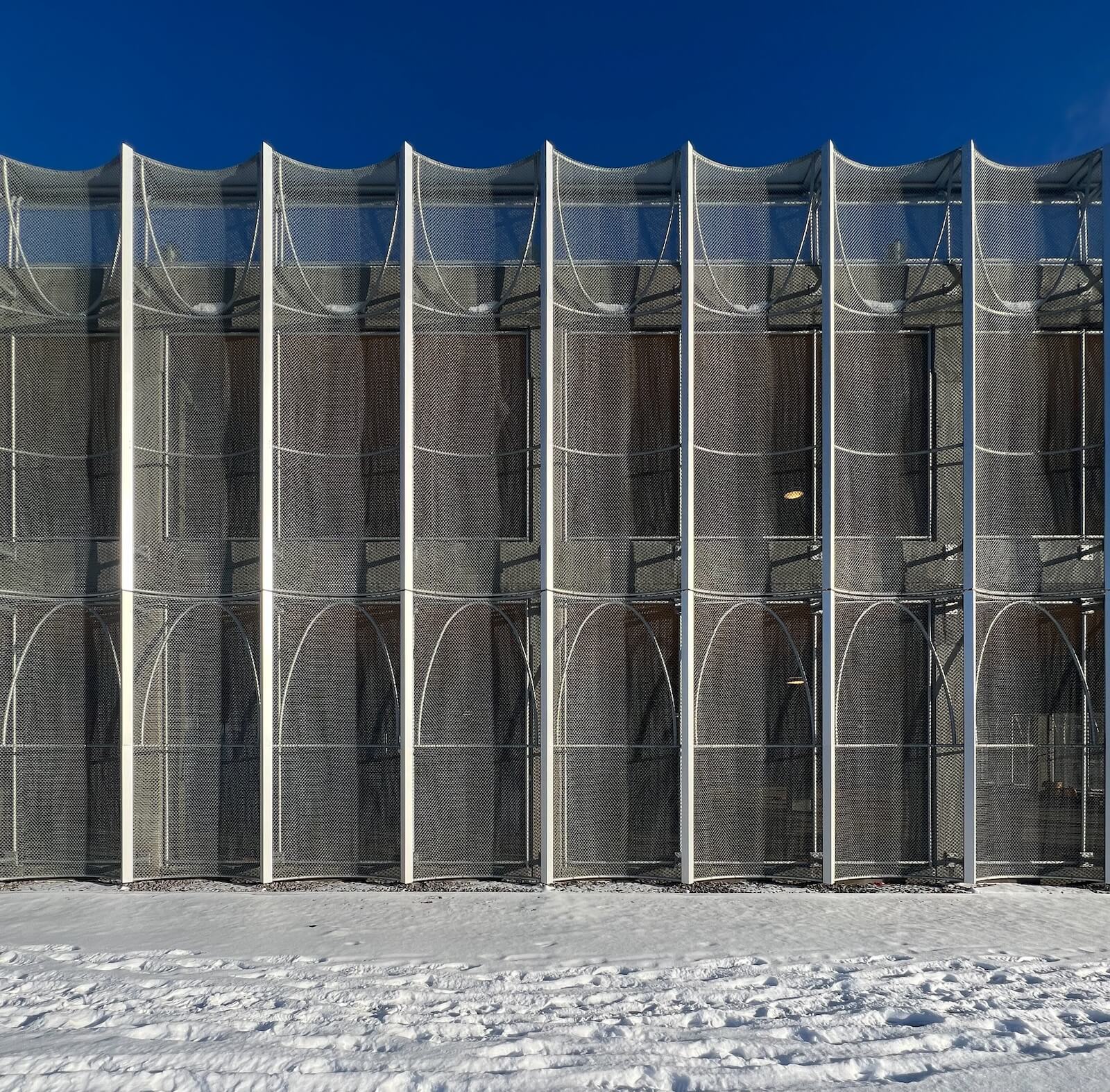

The 4.5-hectare Kathleen Andrews Transit Garage, a heroic building that flaunts its heroism, is clad in stainless steel, which shifts in hue, as the sun recedes, from icy white to amber to blue. The garage accommodates 350 workers and housing 300 buses. Its main feature is a skylit bus lot with a columnless Miesian floor plate. Yet it conveys a grandeur, and an exaltation of public works, that is in tune with Gh3*’s other projects. “The design…argues for an architecture that can perform at the scale of urban infrastructure, at the scale of highways,” the firm explains in the building description.

The Windermere Fire Station, a net-zero fire hall, has monochrome brick cladding textured like the surface of a rattan basket. It’s topped with a simple gable gently sloped to maximize space for solar panels. Beneath the building are geothermal wells, which moderate the interior climate by transferring heat (or coolness) from the ground below.

Perhaps the firm’s most celebrated public work is the Borden Natural Swimming Pool (another Civic Trust winner), which treats water without chemicals. To handle the engineering, Gh3* partnered with Polyplan Kreikenbaum, a German firm that specializes in aquatic systems. Water at the pool is pumped to a gravel bed and then flows through two on-site ponds.

The first aerates the water to stimulate microbial growth; the second shades it beneath lilies, creating a habitat ideal for zooplankton, which eat up harmful bacteria and toxins. The layout — a play of nested rectangles — has the geometric rigour of a Mondrian painting, and the site and its change room facilities are lined in permeable gabion walls, a metaphor for filtration. “With each project,” says Hanson, “we’re trying to do something simple and economical, with familiar materials used in unfamiliar ways.”

That commitment to conceptual clarity is on full display in a recent Edmonton commission, a district energy station for a planned community that will pump heat from two massive underground sewage trunks. The pumping system will reside in a railcar-shaped volume that runs along the ground. An exhaust vent will be housed in a similarly sized adjacent volume, which bends upward. Form follows function. It’s classic Gh3*.

So far, the firm hasn’t had an outsize presence in Toronto — despite a few public commissions, including June Callwood Park, a medley of granite planks, pink vinyl pavers and crabapple trees — but it’s now making an impact at home too. Upcoming commissions include a Tamil Community Centre, condo buildings above and beyond the usual, and a net-zero EMS building (the first of its type to be constructed with mass timber).

And, of course, there’s the folly in the Port Lands. By 1 p.m., the day was getting hot, prompting people to flee the shade-less beach for the sanctuary of the tower. I had a remaining question for Hanson: Why bother to beautify infrastructure at all? After all, it derives its value from functionality. So if it hurts to look at, who cares? It wasn’t built to be looked at anyway.

“Whenever you do anything, you should do it well,” Hanson responded, adding that the marginal cost of good design is miniscule relative to the cost of a building itself. An ugly water-treatment plant is a pricey undertaking; a beautiful one is only slightly more pricey. So why not spend that little bit extra? “Toronto owns hundreds, maybe thousands, of buildings,” she said. “Can you imagine what the city would look like if all of them were beautiful?”

I mentioned to Hanson that, at some point during our conversations, I’d started to sense a connection between her architecture and her life. There’s a recursive element to her designs: They are built to respond to changes in light or to tap into natural processes. Her own story has a cyclical quality, too: Disappointments have given way to breakthroughs, setbacks to life-changing opportunities. “I’ve never really thought about things that way,” Hanson told me.

In Edmonton, two hours behind Toronto, the day was still heating up. But the Windermere Fire Station would remain cool thanks to the thermostatic properties of the earth beneath it. At the Borden Pool, not too far away from the fire station, dirty water was flowing into adjacent ponds. Then it was flowing back clean again.

For almost two decades, architect Pat Hanson and her firm, Gh3*, have been bringing uncommon beauty to sustainable urban infrastructure in Toronto and Edmonton – and she’s only just begun.