For too long, the City of Toronto has outsourced its pollution problem to nearby Lake Ontario. Contaminants include the obvious culprits — raw sewage and industrial runoff — but also stormwater, which the advocacy organization Lake Ontario Waterkeeper calls “a nightmare of an environmental issue.” During rainfall, water runs along the roads and down the gutters, picking up sediment and mixing with oil, fertilizer and pesticides before disappearing into storm drains and into the sewage system. During heavy storms, though, it overwhelms the system and instead gets discharged into the lake.

In 2010, Waterfront Toronto, the public corporation tasked with revitalizing the city’s thoughtlessly built and polluted downtown lakefront, hired Gh3* to design a stormwater-treatment centre in the West Don Lands area, southeast of Toronto’s core. Christopher Glaisek, chief planning and design officer at Waterfront Toronto, wanted the facility to be not only functional but beautiful too. The corporation tapped Gh3* for the job because the architecture practice brings a poetic sensibility to all its infrastructure designs.

Its portfolio includes an LRT station (not yet built) with Romanesque vaulted ceilings, a water-monitoring facility that resembles a massive drum and a transit garage that is both monumental and elegantly minimalist, like the work of mid-century icon Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. “Gh3* can take a modest commission,” says Glaisek, “and pack a whole lot of interesting architecture into it.”

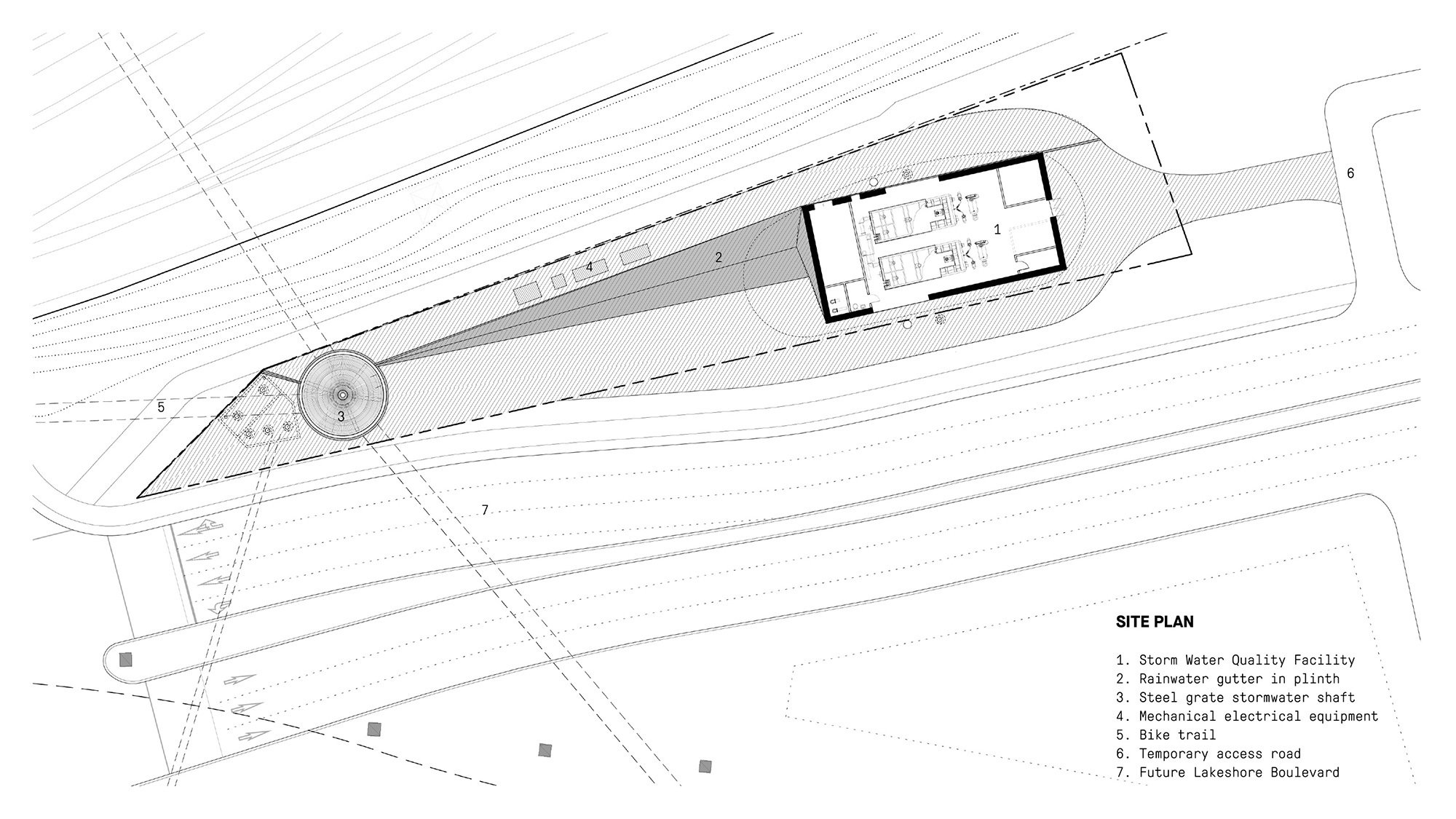

Pat Hanson, a founding partner at the firm and the lead architect on the Storm Water Quality Facility, envisioned it as “an inverted well.” While many cisterns take the form of rectangular pits (yes, they’re not all cylindrical), the building is instead a rectangular extrusion, like a well turned inside out. Moreover, it has the opposite function. Instead of drawing water from the ecosystem, the facility cleans and then safely returns it.

The process is simple. Water from nearby storm drains collects in an underground chamber adjacent to the facility. It’s then pumped into the building, where it travels first through a giant sieve — which removes large pollutants like plastic bags or bits of tire rubber — and then into a tank where it’s injected with polymers that bind to sediment, making these particles sufficiently heavy to sink to the bottom, where they can be easily removed (this process is called ballasted flocculation). Finally, the water goes into another tank, where it’s treated with pathogen-killing ultraviolet light, making it pure enough to go back to the lake.

Hanson’s design is every bit as elegant as the mechanical operations within. The building is a simple, stolid and monolithic concrete rectangle with a prismatic roof. The interior space moves downward — from a high platform on the west side to a lower platform in the middle to a skylit floor space on the east side — following the flow of water as it travels through the system. Exterior ornamentation is limited to a series of square sconces, a few doors hidden behind aluminum fins and a window into the facility to accommodate curious passersby. “To design well,” says Hanson, “you have to be thoughtful about the choices you make.”

Why bother investing in design at all? For Glaisek, a better question is: Why not? “Infrastructure offers an amazing opportunity,” he says. “So much money gets spent on it, but the incremental cost of adding architecture is relatively small. It’s an easy way for cities to make themselves more beautiful.” Some people may believe that, when it comes to public works, any expenditure on aesthetics is by definition profligate.

But in the past, ambitious planners rarely thought this way. Hanson points out that many historic architectural wonders, from the Roman aqueducts to the bridges of Venice to the Hoover Dam, were fundamentally infrastructural in nature. “If you make infrastructure legible and beautiful,” she says, “the public gets interested, asks questions and assumes ownership of what are among the most important buildings in any city.” This is true in Toronto, where arguably the best and most storied edifice is the R.C. Harris Water Treatment Plant, an art deco cathedral dubbed “the Palace of Purification.”

The Storm Water Quality Facility is smaller and less ornate, but it aspires to the same level of aesthetic sophistication as a modernist counterpart to this predecessor. When I visited the 557-square-metre structure with Hanson, she took a minute to inspect an anti-graffiti sealer that had been added to the concrete. “It makes the walls less light and bright,” she noted, ruefully, “but sooner or later, they’re going to darken anyway.” She then noticed a gooseneck vent — an unsightly protrusion on an otherwise simple wall — that was added without her permission. “This has to be taken down,” she said. “I’m trying to keep things clean around here.”

Known for transforming infrastructure into architectural feats, Toronto practice GH3* unveils a stormwater processing facility that doubles as a stoic civic landmark.