The closure last week of the Ontario Science Centre came as a shock. Though there were clear indications the Ontario government has long been planning to shutter the beloved institution, this final, decisive and cynical move – on a Friday afternoon just before the Premier departed for summer vacation – felt like a stinging insult to everyone who is fighting to save the Brutalist icon as well as a tactical move in a much larger political plan. Here, AZURE editors Elizabeth Pagliacolo, Stefan Novakovic and Eric Mutrie wrestle with the manifold implications of this disheartening yet galvanizing moment.

As countless people have pointed out, this is not a story about a failing roof. When the provincial government closed the Ontario Science Centre last week, installing fences around it immediately, it insisted that safety was of the utmost concern. Nothing could be further from the truth. A much-cited engineering report (prepared by Rimkus) on the building’s aging roof did not recommend a closure, instead a schedule of repairs. The costs to fix the failing sections are not prohibitive in any sense, especially when one considers the bigger math at play. And if money is the real concern, many have come forward — from the architects at Moriyama Teshima, offering their pro bono expertise, to venture capitalist Adam McNamara, putting up funding — to absorb the costs involved. As everyone who has been following this story can see (and as Elsa Lam and Alex Bozikovic have reported in detail) the closure of the Ontario Science Centre is the first chapter in a much bigger playbook — the real story. It is a major step in introducing a new, smaller, and we would argue lesser, version of a science centre to Ontario Place — which is the shadow looming over this entire debacle.

The Ontario government is fixated on pushing through with its plans for Ontario Place despite widespread criticism. At the core of its scheme, as everyone is well aware, is a mega-spa by Austrian firm Therme to be situated on the West Island. The weekend the Ontario Science Centre was shuttered, the demolition of several key structures on the West Island of Ontario Place began. To make way for the spa, all of the island’s trees, including over 600 mature trees, will be cut down. Michael Hough’s landscape of lagoons and waterways will be filled in, destroying the aquatic and wildlife that has made its home there. Filling these lakes will allow for Therme to have 12 extra consolidated acres for its mega-spa, which will also require a multi-tier car garage costing the province an estimated $600 million. Already underway, this destruction of a thriving natural habitat, a green public space, and a heritage landscape of great cultural significance is anathema to any progressive vision that our province should be espousing, one that should safeguard our environment and promote walkability, accessibility and public use of public land.

So insistent is the provincial government on moving forward with its plans at Ontario Place that in 2023 it enacted Bill 154, or the “New Deal for Toronto Act,” which includes the Rebuilding Ontario Place Act. This unprecedented act exempts the provincial government from adhering to the Ontario Heritage and the Environmental Protection Acts, among other measures, while shielding it from any liability for “acts of bad faith,” “misfeasance,” or failure to meet any “fiduciary obligations.”

While Bill 154 mainly deals with Ontario Place, its woeful spirit is key to understanding what has happened at the Ontario Science Centre: Here is a government that will enact legislation giving it sweeping powers to undo Ontario’s heritage and leave dissenting voices no recourse. All this in the aftermath of a failed attempt – due to public outcry – to award developers swathes of the Greenbelt, lands featuring farms, forests, wetlands, rivers, and lakes that are crucial to our food supply and climate change mitigation.

As for the Science Centre, the government has put forth an argument that the land surrounding the building will be developed with housing. “We want to create as much density as possible,” Premier Doug Ford has said. “There’s going to be thousands of units there.” By locating an Ontario Line subway terminal at the science centre, he argued that the government was espousing “transit-oriented communities.” Yet the actual, ethnically and economically diverse, community of Flemingdon Park, where the Ontario Science Centre resides, has never been part of consultations on such plans.

Dual obsessions of the provincial government, Ontario Science Centre and Ontario Place are prime examples of its trend of privatization via neglect – allowing public goods to deteriorate in order to justify their misguided replacements. The Ontario Science Centre is an iconic, much-loved and much-used architectural landmark, but one that needs TLC — and, in fairness, was already in dire need of an update and renovation before Ford came into power. The powers that be won’t hear of it. In a report on the building, the Auditor General clearly states that “deferred maintenance projects that were at risk of critical failure have been repeatedly denied funding.” This pattern of defunding, neglecting and then privatizing is a tried-and-true tactic of a provincial government that feels it has to answer to no one. By Elizabeth Pagliacolo

In government, Friday afternoons are a good time for bad news. For politicians the world over, the end of the work week offers a potential reprieve from the intensity of public scrutiny, with the weekend often diluting the wave of controversy, media attention, and public outcry that follows an unpopular announcement. Last week, the Ontario government served up a shameless classic of the genre when it announced the abrupt closure of the Ontario Science Centre — and seemingly for good. But it didn’t go quietly. Over the weekend, protestors, activists and politicians filled the grounds, as media outlets across the country and beyond reported the news. Summer vacation wasn’t starting just yet.

By Monday, a pall of outrage spread across the civic horizon. Then, on June 26, a new Infrastructure Ontario RFP set out the scope of a costly yet substantially smaller temporary facility, while up to 50 food service workers are poised to receive imminent layoff notices. As the tolls mount, Canadians of all stripes are sharing their stories and voicing their concerns. They span the practical and the sentimental, from the temerity of needlessly shuttered summer camps to the nostalgia of cherished childhood memories. Amidst the debate, the merit and meaning of Raymond Moriyama’s design is once again under the microscope.

And there is much to be said, whether about the carbon costs of demolition, the relatively uncomplicated feasibility of renovation, the logistics of keeping much of the facility open while the roof is repaired, the expense of temporary relocation, or the fonts of cultural memory embedded within the concrete walls. Yet, the naysayers persist. Though beloved by many architects, mid-century buildings writ large are on the demolition block the world over — often with public indifference or outright support. Writing in support of the Science Centre demolition in the Toronto Star, columnist Heather Mallick summed up a popular sentiment with graceless concision: “Brutalism is ugly.”

She’s far from alone. In a 2019 social media poll, for example, Toronto Star readers widely nominated brutalist icon Robarts library as both the best and ugliest building in the city. It topped the latter category. Describing brutalist buildings as an example of “architectural manspreading that nobody loves,” Mallick characterizes the whole of the mid-century design movement as “huge monoliths to overawe pointless little humans.” The architecture of the Ontario Science Centre tells an entirely different story — yet one that takes some understanding.

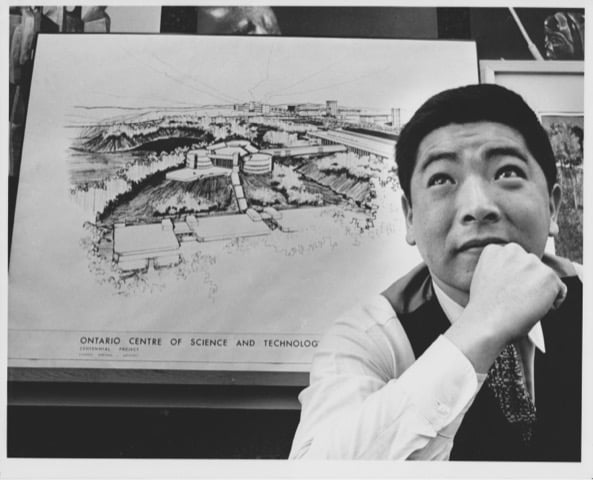

Conversations about aesthetic preferences tend to end in an impasse. While government communications, engineering reports, carbon costs and procurement practices can be debated on reasonably tangible merits, there’s truth to the cliché: Beauty resides in the eyes of the beholder. But maybe there’s a way to see with different eyes. Here, too, Raymond Moriyama is an inspiration. While the late architect is renowned for the elegance and élan of his profoundly public buildings, he was also an uncommonly gifted architectural communicator. In explaining his work, Moriyama translated his aesthetic and programmatic choices into the civic values they embody. Notably, the Science Centre was designed as a first-of-its-kind participatory cultural hub, one where touch, feel and interaction replace the rigid hierarchy of display cases and red velvet ropes. “When you hear, you forget; when you see, you remember some; but when you touch and do, it becomes part of you,” said Moriyama.

Inspired by Confucian philosophy, Moriyama designed the Science Centre as “more than a place to keep artifacts,” but as “a place where hands-on experience would be fundamental to how people learn.” Imbued with the spirit of wonder and discovery, the building’s circulation translates the excitement of scientific discovery into every visitor’s journey. What better way to inspire tomorrow’s innovators? And while the exquisitely textured brutalist walls are shorn of frill and ornament — erasing signals of status and class position — the complex opens up to majestic views of the verdant ravine landscape, situating human discovery within the living, breathing earth. The exhibits needed updating, but as a visitor, the effect remains both humbling and inspiring. Any of us can become a scientist. All of us are part of something greater.

Moriyama’s buildings are like that. They convey us through an emotional journey that renders the architecture legible. All it takes is being there — and maybe a little bit of explaining. And Moriyama was awfully good at explaining it. For the architect, the Science Centre was a turning point. “Every building we’ve worked on since then has had a similar process of taking an idea beyond simply architecture,” he told AZURE in 2013. In designing the Scarborough Civic Centre, for example, the architect offered a sly elucidation of how the building supports egalitarianism and civic disobedience: “the Mayor’s window is low enough you can throw a brick right through it,” he said, translating architectural language into latent civic action, and a window placement into a legible political statement. Yet, few of us share his gifts.

When I started out as an architecture journalist, I often found myself lost for words. While I picked up plenty of professional jargon and quickly learned the aesthetic signifiers of prevailing design industry tastes, I lacked the means to translate it into a broader, more accessible language. One night, about a decade ago, I was sitting at a patio in Toronto’s Kensington Market with a friend and remarking on the ugliness of the colossal condominium tower that loomed above the street. My friend, a pharmacist, said he liked it just fine. So what made it so bad? I didn’t know how to explain, which left me wondering whether all that architectural language and good taste had really taught me anything.

A day later, I relayed the story to my architect brother. He gave me some advice I won’t soon forget. Imagine the condo tower as a human being, and then ask yourself: What kind of qualities would this person have? I thought about it. If the tower was a person, it would be loud, brash, overbearing and self-absorbed, practically begging you to crane your neck up and look at its rooftop lights. Was it an objectively correct take? Of course not — after all, our opinions about people vary even more than our opinions about buildings. But it was articulated in a language we can all understand.

It’s been on my mind. Reading Mallick’s column, I’ve been wondering how to respond to the invocation of ugliness. It prompted me to return to the same exercise: If the Ontario Science Centre was a person, what kind of person would they be? I think they would be generous, tolerant, open-minded, friendly and a little bit playful. In other words, I think they’d embody the graces that so many of us celebrate as quintessentially Canadian. I think they would be beautiful. And I think they would deserve a long and happy life. By Stefan Novakovic

It can be easy to feel powerless while watching a government carry on with its agenda undaunted in the face of so much public outrage. But there is still value in adding your voice. There is value in expressing your support for the Ontario Science Centre by promoting the building’s many merits and galvanizing others to do the same. To date, there has been no public consultation on what should be done with the building — but we must nevertheless make the cry to “Preserve it!” the sentiment with the loudest possible majority.

Why? Hopefully by this point we have sufficiently established the rich beauty of Moriyama Teshima’s design. But we also believe that a museum dedicated to science simply cannot ignore the negative environmental consequences of demolishing a large concrete structure full of embodied carbon in favour of new construction. In its own coverage of the Ontario Science Centre controversy, the National Trust for Canada states unequivocally that “trashing structures and their materials is a luxury that Canada can no longer afford.” The most meaningful opportunity for greenhouse gas reduction is to make use of our current structures. In short, “the greenest building is the one that already exists.”

Similarly, the current Ontario Science Centre site affords a rare opportunity that cannot be matched by a new location at Ontario Place. Positioned next to a soon-to-open transit station on the upcoming Line 5 Eglinton light rail system, the current building is located on a remarkable ravine that functions as its own form of living ecological exhibit. An upcoming station on the Ontario Line subway would strengthen the building’s accessibility even further. Moving the Ontario Science Centre to Ontario Place would also sever the institution’s deep ties to its surrounding Flemingdon Park neighbourhood, with no clear advantage in terms of location.

Finally, there is the long cultural legacy embedded within the building’s brutalist halls. It is thanks to adults who once found childhood inspiration at the Ontario Science Centre that many scientific miracles — be those surgeries, solar power, or major feats of engineering — are now made possible each day. In turn, the kids who first visited the Ontario Science Centre earlier this year deserve to be able to someday bring their own children to that same landmark — and they deserve to arrive at a building that maintains the same sense of wonder that our ancestors felt on their own first visit back in 1969.

For the sake of sustainability, community, and cultural heritage, the Ontario Science Centre must be repaired and preserved on its current site. Please join us in supporting this cause and demanding our government take steps to protect this rare architectural landmark.

Below are six recommended resources for moving this cause forward:

- Add your support to Save Ontario’s Science Centre’s public letter, which as of June 26, 2024 has been shared with Premier Doug Ford by almost 50,000 individuals.

- You can also contact Premier Doug Ford directly to express your feelings about this decision.

- Fight back against the idea that closing the building was the only possibility by sharing media coverage disputing this claim. As Alex Bozikovic summarized in his Globe and Mail editorial, “closing the Ontario Science Centre is a choice” — not a necessity. Do not let the dominant public narrative about this decision become one that obscures the truth.

- Promote the various financial offers from those willing to privately fund the cost of the building’s rehabilitation or to offer their design services pro bono. We must dispute the government’s position that renovating the building is too expensive and that there is not sufficient funding available. In your letters to the provincial government, ask politicians why they are not taking these individuals up on their offers.

- If you are a designer, refuse to participate in the Infrastructure Ontario RFP seeking an interim site for the Science Centre until a plan is in place to restore the current structure. Instead, submit letters to those running the procurement process urging them to pursue an alternative approach making use of the existing building. The design community needs to stand together in obstructing a replacement Ontario Science Centre from moving forward.

- Defend what remains of Ontario Place by promoting the efforts of Ontario Place Protectors to seek an injunction to the demolition that began on June 23.

By Eric Mutrie

***

Do you have additional resources, strategies, or ideas, about how to save the Ontario Science Centre? Get in touch with us at azure@azureonline.com, and we’ll update the article with additional links. (Last updated: June 27)

Lead image by Dennis jarvis via Flickr Commons.

A three-part look at the politics, architecture, and activism that informs the sudden closure — and future — of a beloved Toronto institution.