Until recently, 3D-printed construction and traditional earth buildings existed at opposite ends of the technological spectrum. But an innovative Forest Campus in Barcelona’s Collserola Natural Park, developed by the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC) with international architecture firm Hassel, combines the best of both worlds, marrying cutting-edge techniques with vernacular design. The product of over one decade of research, the 100-square-metre structure is a full-scale prototype for sustainable and affordable construction. Though 3D-printed architecture is typically made of carbon-intensive concrete, the Forest Campus was printed on-site using local soil and natural materials sourced from just a few metres away — and completed in only 10 days.

After being dried in the sun and sieved to filter out large stones, the earth is mixed with water, organic fibre and natural enzymes. This mixture is then pressed into the 3D printer and extruded at a rate of 25cm height per day, to avoid the structure collapsing under its own weight. The 3D-printed earth walls sit atop a stone foundation, for stability and drainage, and a thick, stabilized earth base, which offers flood protection. The walls’ thicknesses, which vary from 40 to 70cm are determined by the load they need to carry and the solar orientation. Once the walls are partially dried, the timber roof can be installed, anchored to the walls to avoid uplift from the wind (or post-tensioned with steel cables down to the foundations).

While the porous earth walls make for a striking architectural feature, their design was more than an aesthetic choice. Their cavities reduce material use, support passive design strategies like natural ventilation and lighting, and enable the integration of insulation and services; plus, their material composition helps regulate heat and humidity. Though especially effective in warm climates like Spain, the technology has the potential for global application: Hassel is leveraging the construction method for a community building in Tanzania, set to be completed later this year. — Sydney Shilling

Since October 2022, a group of strange creatures has been gathered off the coast of Clifton Springs, a seaside town on the Bellarine Peninsula in Australia. But while the 46 masses possess the eerie beauty of deep-sea animals, they are far from an invading species intent on doing harm. Quite the opposite, in fact. Developed by industrial designer Alex Goad and his team at Melbourne-based Reef Design Lab, the curious objects have been installed as part of an ongoing campaign, with the City of Greater Geelong, to rehabilitate the area’s marine ecosystems.

Called EMUs — or Erosion Mitigation Units — the 200-centimetre- wide, 1.6-tonne dome-shaped modules are precast in specialized moulds; made from locally sourced recycled shells and low-carbon concrete (cement combined with 30 per cent fly ash), they serve a threefold purpose. First, to aid in the alleviation of shoreline erosion, the EMUs provide wave attenuation that reduces the height and energy of incoming waves. Second, their rough texture and intentional nooks, crannies and holes support and offer protection to a range of marine organisms (even when the tide is low, the small rock pools remain filled with water). And finally, they create an underwater sculpture park for snorkellers, scuba divers and swimmers to explore.

While the man-made reef is still being monitored and its benefits measured, a second troupe of EMUs has already been installed further northwest near Kingscote, Kangaroo Island, signalling the positive impact the artificial structures will have on the natural environment. — Kendra Jackson

“Amid a biodiversity crisis with an alarming decline of pollinators, municipalities should be making it easier, not harder, for residents to foster gardens where native plants thrive,” says Lorraine Johnson, the cultivation activist and writer. Johnson is part of a team urging local governments across Canada to support — and promote — the planting of vibrant, regenerative gardens as an alternative to water-intensive manicured lawns.

In Canada and beyond, green thumbs and change- makers alike are trying to bolster biodiversity at home, turning to their own front yards to grow gardens with native plants and pollinators. But municipal bylaws thwart the creation of these naturalized spaces, dubbed “habitat gardens,” and put up barriers at odds with sustainable practices — often without meaning to — by banning weeds without specifying the species, enforcing arbitrary lawn heights when sightlines aren’t an issue, and more. For designers, these regulations dampen the effects of biophilic principles. For everyone else? The loss is just as deep.

In July 2024, a group of dedicated conservationists — comprising Johnson herself, along with the Canadian Society of Landscape Architects, Canadian Wildlife Federation, David Suzuki Foundation and Toronto Metropolitan University’s Ecological Design Lab (run by Margolese Prize laureate Nina-Marie Lister, whose garden is shown here) — published an open letter addressed to Canadian municipalities calling for the support of habitat gardens. Part of a campaign for municipal environmental leadership across Canada formed in 2021 called Bylaws for Biodiversity, the letter demands that Canadian leadership reform the rules, commit to educating the community, properly train bylaw enforcement and, most of all, lead by example. If our cities blazed the trail, there’s no telling what flora and fauna would appear — right on our own doorsteps. — Sophie Sobol

In the southern Taiwanese city of Tainan, the Taisugar Circular Village proudly shows its seams. Designed by Bio-architecture Formosana, the masterplanned community unfolds in visible modules of prefabricated panels, an exterior steel structure and solar panels prominently affixed to gable roofs. Envisioned as a test bed for circularity, the transit-oriented 351-unit development optimizes ease of maintenance and replacement — in essence, it’s a system that can be taken apart and reassembled with little more than a socket wrench and a screwdriver.

While the sociable site plan incorporates urban agriculture, communal cooking and a farmer’s market, as well as a resident-led repair studio, the architecture is thoughtfully pared down and catalogued. From the kitchen cabinetry and electrical wiring to the partitions between units, prefab facade system and structural core, the design allows for streamlined, isolated fixes, eliminating the need for welding, glue and demolition, all while incorporating low-carbon materials, including salvaged timber. Moreover, every building component used is tracked via an exhaustive material library, allowing discarded elements to be returned to their manufacturers and recycled. — Stefan Novakovic

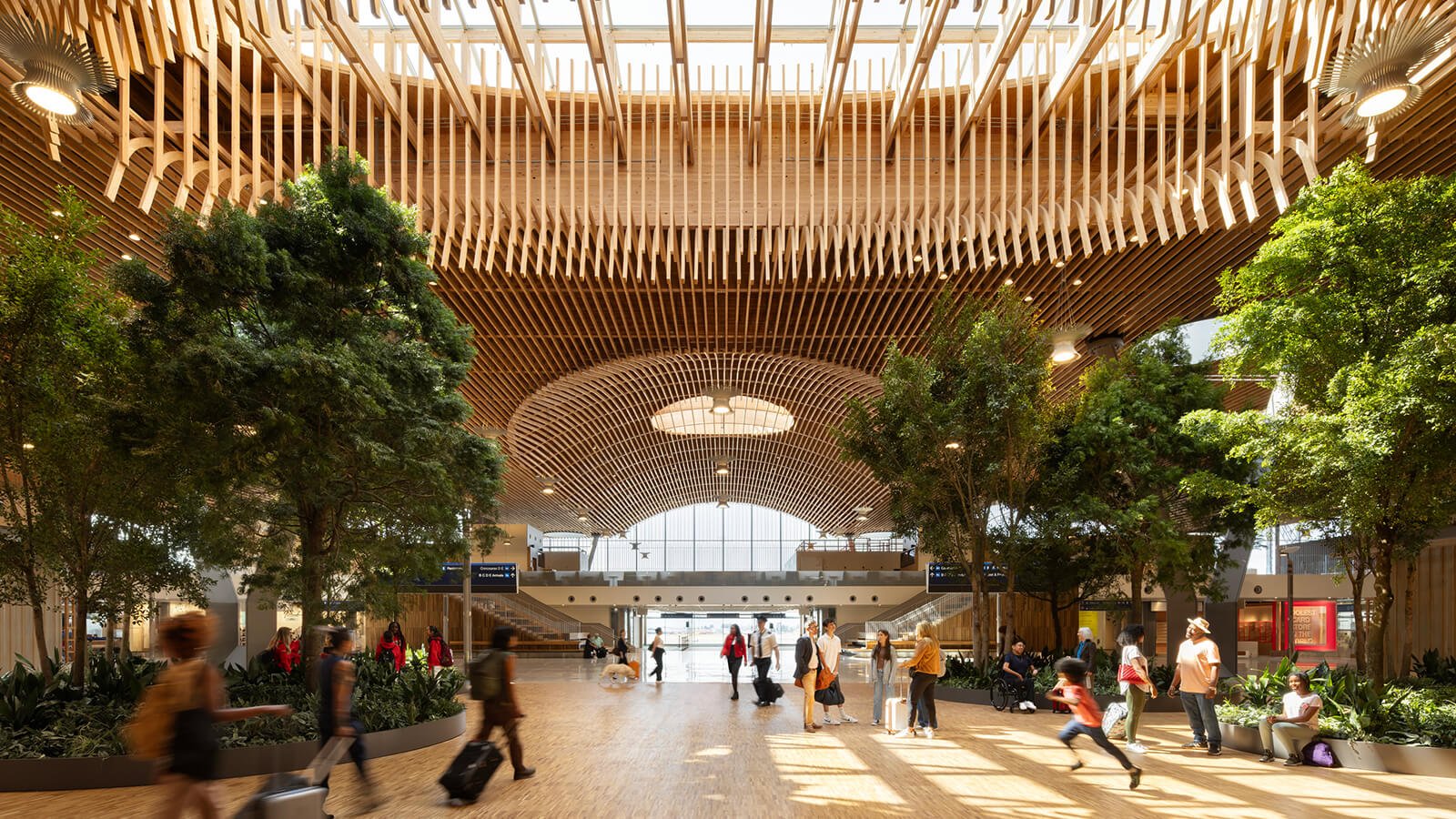

Portland-based ZGF Architects is a frequent flier at Portland International Airport, having led the transit hub’s first major expansion plan all the way back in 1966 and overseen many subsequent renos in the years since. Now, it has embarked on another long-haul journey, doubling the size of PDX to prepare it to accommodate some 35 million annual passengers by 2045. Impressively, it is executing this expansion while also halving the airport’s energy use per square foot — thanks largely to an all-electric ground-source heat pump system.

The showpiece of the reimagined Main Terminal is an undulating mass timber roof that spans 3.64 hectares. All wood was sourced within a 300-mile radius from responsible suppliers that include the Yakama Nation–owned Yakama Forest Products. Continuing the showcase of the Pacific Northwest’s natural beauty, pathways are landscaped with some 5,000 plants and 72 trees — using biophilia to transform an often stressful environment into a calming oasis.

On the other hand, critics like architect Michael Eliason (founder of the green think tank Larch Lab) have pointed out that the airport’s reductions in embodied carbon will be undone by just 23 days of flights between Portland and Seattle, which are only a three-and-a-half-hour train ride apart and could be made even closer by a high-speed route. If we really want to make airports more eco-friendly, we need to start by integrating them into a larger transportation rethink. — Eric Mutrie

In the 1850s, the Chicago River became a casualty of the city’s industrial progress as pollution from steel mills, lumber yards and meat-processing factories (among other enterprises that made their home along the riverbank) emptied into its waters. “Most astonishingly,” notes the architectural firm SOM, “the River’s flow was reversed to send the city’s sewage downstream in 1900, a move which has impacted the ecology of Lake Michigan, the Mississippi River and their tributaries ever since.” Part of a larger restoration project to remediate this amphibious landscape, the Wild Mile is an initiative by SOM and Urban Rivers.

The floating eco-park, the first phase of which was completed in 2021, resides in the North Branch Canal, where it provides a new gathering space and river access to the entire community. The living laboratory has also become a hub for the River Rangers, or “citizen scientists,” who collect data on plants, wildlife and other phenomena in the area — from the 99 bird species clocked here to the thousands of pieces of trash (carelessly) left behind by visitors. The boardwalk’s kit of parts includes various modules — overlook, path, pier, access ramp, habitat rafts, and activity and classroom platforms — that allow it to scale up. Envisioned to expand, the initiative has just completed its second phase, which doubles its original size. — Elizabeth Pagliacolo

A look at inspiring projects around the world that embrace new ways of building, planting and remediating for a greener future.